Best Quality Products

Welcome to The Online Chemists!

We make sure your life-saving medicines are convenient, accurate and easy. Give us a try and let us help you simplify your life.

Free Delivery

Above $999 Only

Bitcoin Payment

$20 off on paying through Bitcoin

Secure Payment

We follow trusted payment method.

24/7 SUPPORT

Experince our best support system

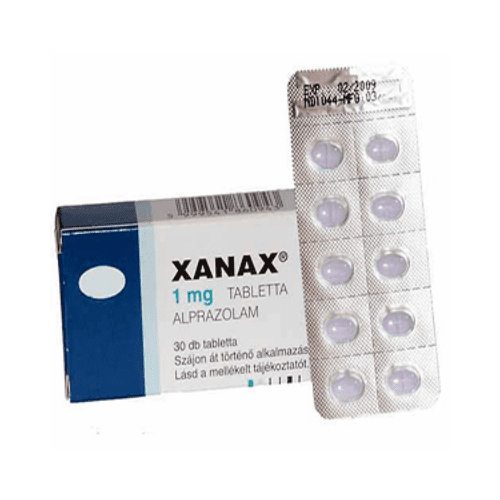

Best Selling Products

Get $20 Off Paying Through Bitcoin!

About The Online Chemists

Managing your medications and drugs is not always easy. However, at The Online Chemists smartest, we endeavour to prioritize your health. Moreover, we do this by working around your convenience. In addition, our excellence services meet standards that make patients happier and healthier.

To support the vulnerable members in communities, we have competitive services to simplify the process of online orders. The Online Chemists are a licensed pharmacy offering a wide range of drugs online.

Our Values

We ensure not to share any of your credentials and discreetly provide you drugs at your doorstep. Moreover, our safeguard ensures that the prescribe proactively shares all relevant information without any issues.

Whether it’s late-night or early morning, you can shop for medications at anytime. That being the case, you will never encounter closed store signs or long queues while buying with us. We assure you that your medication reaches within you in 48 hours.

Your privacy is taken seriously. Therefore, we do not share any data with third parties. Furthermore, your medical notes are safe and accessible by our doctor or pharmacist.

Our druggist has a dedicated customer services team to answer your queries. As such, for any questions or help, our experts are available for 24 X 7 online support.

Our Online Services

Neglecting your drugs is risky. However, it can happen in our fast-paced lives where we become so caught up in our obligations. As such, our role is to protect customers and ensure they received safe and effective care by using our services online. We are a licensed and independently-verified pharmacy partner. Our assurance is that our customers experience peace of mind.

Ensuring that the life-saving medicines in are store are convenient, accurate and easy is important to us. Give us a try and let us help you simplify your life.